All about every d2c brands' dream - cracking offline retail

I start this post by asking you to visualise 2 scenarios in your local retail store or a supermarket - one where you go back to the 2000s and the other where you see the same from 2024.

Whats hasn’t changed? You will see the same old legacy FMCG brands in both the images - be it Surf Excel, Lux, Britannia, Amul and so on.

What has changed? The sheer variety of products has boomed - you will find far more items and far more brands now. One distinguishing feature of the shelf from 2024 is that you will probably find more new age “d2c first” brands than the legacy brands. You will see a high churn rate, new brands keep coming and going with time.

There is an explosion of d2c brands in India and some d2c founders have also become mini celebrities themselves. Shark Tank India is a perfect example where both of these are juxtaposed in the same frame.

If you are a d2c brand in India, you generally start off by selling through your own website or even WhatsApp/Instagram, try cracking marketplaces like Flipkart/Amazon/Myntra etc after you reach a certain scale. However, it is known that despite the rapid growth, e-commerce still commands only ~10% of the overall retail landscape in India.

Also, you face intense competition when you try to grow beyond a point, thanks to competition from other brands for both - the top ads slot (competitors need bid a certain amount to get better visibility on Google, Amazon etc) and also the attention of the limited set of online shoppers.

In this competitive landscape, if you want to grow further in size, you have 2 options -both of which have certain entry barriers - start selling abroad or try to sell in the world of offline retail.

While selling abroad has become relatively easier in recent years, there is a still some challenge in terms of compliance, getting entry in various channels and unit economics.

You may also realize that a large segement of your potential customers would still like to touch and feel the product before purchasing it (even if they eventually buy it online)

So the next obvious target for a d2c brands is to crack offline retail.

The flowchart above tries to illustrate the lifecycle of a brand in terms of the new channel that may become necessary to cross that revenue thresholdUnit economics of offline retail

Before we get into a critical analysis of what it takes for a brand to succeed in offline retail, let’s look at the unit economics of offline retail. Obviously, all the type of channels want to list products that sell, so that is a given while I get into more details below -

Note - this is an illustrative example only, the margin structure varies significantly by your category - the margins for staples like atta/rice or electronics are far thinner than the margins for personal care products.

Large Discount Stores like Dmart- they care primarily about only 2 things - volumes and the best price to customer (ASP) in the market. A brand can afford to sell on Dmart at the cost of earning a thinner margin that needs to be made up for by selling in large volumes. It really is the survival of the fittest

Organized Chain Stores like Nature’s Basket/More/Spencers/Namdhari’s Fresh/Reliance Retail- These chains are not heavy on discounting, their real way to make money from you (which also acts like a entry barrier) is by charging listing fees in which they charge upfront fees and promise some extra visibility as an added on bonus. These can be a flat one-time charge of say Rs 10L OR 1L per month OR a flat one-time charge of Rs 10k per unit per store. This will lead to 2 outcomes for a brand -

You need to work out what is the minimum volume that you’ll need to sell in a year or so to break even. For example, you need to pay Rs 10L to gain entry into some national chain, the avg. sale price from you to that chain is Rs 250, your margin per unit is Rs 50 and you want to end up earning Rs 30 as your final margin per unit after paying 10L worth of listing fees. How many units do you need to sell for that to happen? The math is shown below -

Assuming that there are 50 stores where you get listed and each store sells 2 units per day, you will need 1.4 years to recover your listing fees. Can you afford that 10L worth of investment? Also, what happens if your sales run rate goes down to 1 unit per day or even lower after sometime? These are the risks to be kept in mind before you take a leap of faith. There are additional risks that I will cover later on

Kirana Stores/General Trade -

I’ve written an article on “Why Kirana Tech is difficult to crack” a while ago which you may find a useful pre read to understand the world of kirana stores a little better.

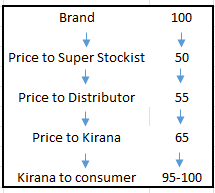

The only real thing kirana store owners care for is rotation of inventory. They want to buy a small amount on credit from a distributor, ensure it sells on time and then buy another batch of small quantitity in another batch. Anything that does not sell goes back to the brand at their own cost. The risk therefore for brands is to ensure that products don’t sit and catch dust on shelves and actually get picked up. A sales person might try to use merchandizing to make the product a little more visible or offer attractive margins to the shopkeeper to incentivize him to sell it. This is an illustration of how the network and margins work in this category.

The other things to keep in mind while determining the unit economics-

What is the size of your salesforce that you need to ensure that your geographical reach expands, you open more stores and your product is available and visible in these outlets?

What is the leakage due to damages and expired goods in your field and how can you control it?

What is the extra marketing, be it visibility aka “brand marketing” or schemes aka “trade marketing” that you need to sustain and grow this channel?

So why do few brands succeed in this space?

The risks are manifold and I’ll try to list some of them here

There are leakages aplenty in this space. The world of e-commerce is a little more orderly - its easy to keep track of your margins, spends and so on in the online world but its difficult to keep track of the same in the offline world and you need a different finance DNA to manage this - what happens when a random salesperson promises a distributor some unauthorized benefit and one fine day, he quits the company and then someone else needs to clean up the mess he/she has left behind? How do you know that the benefits you announce through trade marketing schemes reach the kirana store or distributor and is not eaten up in the middle?

What happens if your product, especially those with a limited shelf life, does not sell? The kirana/supermarket will only pass on the losses to the brand

What happens if the distributor/kirana does not pay their dues or disappears from the face of the earth? Will you send gundas behind them? Or will you try taking the difficult and never-ending legal route?

How do you ensure that your product is not out of stock?

Offline retail, especially in kiranas have limited shelf space and its important for the brand to stand out to some extent - either your brand needs a great recall, have some really innovative packaging or be cheaper vis-a-vis a competitor with the same product. Can you either invest into brand building or create a product with the lowest cost of goods sold (COGS) to be able to compete on price?

This is an image from a "beauty store" that sells personal care products. Look at the number of brands and products - how can you make your product stand out? The image below is a simple example of merchandizing and branding where you need to pay that store owner a little bitAt the same time, you face competition from incumbents for that limited shelf space - what makes you think that your competition won’t play dirty to defend their shelf space?

This is a story I was told during a "pre-placement talk" during my MBA days when a large Indian conglomerate was on campus. The speaker was trying to boast about his employer's market power and the story went something like "Our competition, a large multinational was scheduled to launch in Bangalore city in the following week. We got news of this and got our salesforce to buy out all the available inventory with the shopkeepers on the day just before the launch date. We took it to the outskirts of Bangalore and burned the entire lot". Playing hardball and how.Salesforce management is critical -

You need to hire as you grow and can’t frontload the hiring

You need to manage the training, incentives and the crazy attrition that you see

You need to create beatmaps that ensure the best possible store coverage that can be done by a salesperson (something that large FMCG companies are masters at)

Geographical expansion - you would rather better depth in 3 markets than get half that depth in 6 markets. The snapshot below from a post by Arindam Paul of Atomberg summarizes it perfectly -

A rookie mistake done by many upcoming markets is to dump stocks aggressively in the market hoping that it will automatically get picked up. It may ultimate lead to large returns back to you, some of which may become unsellable. You also antagonize your distributor partner and the word soon spreads in the market to the other distributors

If you want to start a company owned store instead - it all boils down, yes you got it right - to unit economics! Where do I look for a store? How big should the store be? Do you even have the money to pay those upfront deposits? Can you afford to sell enough to recover the rental and staff costs? If you are opening a store to also enhance brand visibility, how do you define your success?

A lot of digital first brands have thought deeply about point number 7 above and decided to go for and “omnichannel” strategy - this is especially true in personal care or apparel with the likes of Nykaa, Sugar Cosmetics, Lenskart, Caratlane etc

As I write this blog, its results season on Dalal Street and companies like HUL, Dabur, Nestle and the likes are delivering stinkers.

It appears that the lofty valuations are finally catching up to them and the management is coming up with excuses such as the one shown below.

A met a friend of mine who works at a large multinational foods company and she said that her company is struggling off late. Amongst other reasons, she said "Arre yaar, yeh Phoodfarmer ne hamari baja di hai" I think the real reasons are manifold - yes, there is a consumption stagnation that is likely taking place. But one other key reason is that in the age of the internet, newer brands are slowly eating into the market share of these incumbent brands.

India has barely seen any real new brand come into the market till 2010 or so but the last 10-15 years has seen an explosion. Yes, some of them are not as good and “natural” as they claim but most of them are superior, either in quality or imagination, to existing incumbents and are eating into the market share of incumbents or are creating new categories by themselves.

Some brands will burn their hands and bite the dust after entering the vast and murky world of offline retail while their products gather dust but the remaining that survive - shall continue to disrupt and hopefully thrive.